Joseph Paul Vorst (1897–1947)

Joseph Paul Vorst (1897–1947) was arguably the most culturally significant Latter-day Saint painter of his time. His work was exhibited or collected by noteworthy institutions, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Whitney Museum of American Art, the Art Institute of Chicago, the San Francisco Museum of Art, and even the White House.

Many Latter-day Saints are familiar with the work of Vorst’s contemporaries Mahonri Young, LeConte Stewart, and Minerva Teichert—but who was Joseph Paul Vorst, and how does his work contribute to the artistic legacy of the Latter-day Saints?

Early Life in Essen

Joseph Paul Vorst was born on Saturday, June 19, 1897, and was the seventh of ten children. His parents, Paul Johan Josef Vorst and Christine Wißkirchen, lived in Essen, a city in the Ruhr Valley that was filled with factories and forests and was 20 miles outside of Düsseldorf.

In 1941, Vorst wrote a brief history of his childhood as the introductory text for a solo exhibition at New York City’s ACA Galleries, and it is the sole surviving autobiographical text of his early home life and education. He said:

My father, a cabinet maker, could not always find sufficient work and it was necessary for my mother to find ways of adding to the family income.

We lived in the country and raised goats, pigs, and chickens, but more important was a big potato patch and vegetable garden. My mother, older sister, and later myself pulled the garden produce in a primitive hand-wagon three times a week to the city market where it was sold. It was not always sunshiny weather and often in the snow and sleet the vegetables froze and our hands and feet were frostbitten.

Vorst became interested in drawing at an early age, and despite his family’s limited financial resources, his father managed to send him to art school. Vorst recalled:

I was not very old, however, before my father found that I showed talent in drawing with pastel and managed to send me to an art school aided by several scholarships which I was fortunate enough to have awarded me. Although I did not have to pay any tuition, I nevertheless had to supply my own art materials. Of course, most of the time it was impossible for me to buy these materials and so I picked up from the floor of the schoolroom pieces of charcoal and thumb tacks away. For drawing paper I used the back side of wallpaper. . . . My work was of such quality that the school has kept it for exhibition purposes.

Vorst’s professional training began at the Essener Handwerker-und Kunstgewerbeschule [Essen School of Trades and Applied Arts], later called the Folkwang School. His studies included architecture, printmaking, poster making, nature studies, and decorative painting. He gravitated towards commercial printmaking, particularly letterpress and lithography. After graduating, he remained at the school to teach.

Vorst embraced modern approaches to art. The first art museum in the world dedicated to modern art, the Folkwang Museum in Hagen, Germany, was only two miles from Vorst’s home and was connected to his school. His exposure to the most daring German painters of the day was likely broad and profound.

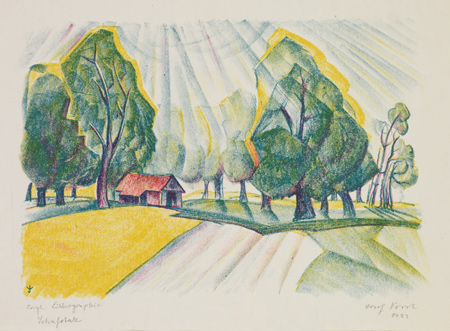

In Furrowed Fields (1922), a posthumously titled lithograph, strong geometric rays from the sky dominate the picture plane. The brightness of fractured light causes yellow shapes to illuminate out of the trees and casts bright shadows on the earth below. It is modernist in its stylistic approach and is laden with meaning, the sun taking on a benevolent role and the heavens seen to be active below. This motif of an expressive sky effecting (and aware of) the landscape below, is repeated throughout Vorst’s lifetime. This effect is also seen in an undated, lost painting from circa 1925 that depicts the appearance of the angel Moroni to Joseph Smith.

Conversion

On June 10, 1924, Joseph Paul Vorst was baptized a member of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. While his conversion story is unknown, records show that he was baptized just four weeks after the death of his brother Karl Paul Peter Vorst, age 23, who was only four years his junior. No members of his family followed him into the faith. Vorst was baptized by E. Neil Burton of Utah and confirmed by Joseph S. Gasser of Idaho.

During the following six years, Vorst’s name appeared more than 134 times in Church records. He taught youth groups, offered prayers in meetings, passed the sacrament, gave sermons, accompanied hymns, and performed as an organist on a harmonium. The Essen Branch records provide a nearly week-by-week accounting of the artist’s whereabouts.

Between 1927 and 1930, Vorst created a large number of linoleum cut prints of scenes from the New Testament that tell the story of the final week of Jesus Christ’s mortal ministry. He later exhibited 40 of these block prints in Salt Lake City, Utah. They were thought to be completely lost until 2016, when a collector in Germany found an old portfolio in an antiques shop that included seven of these prints. The seven prints are the only known copies.

To America

The Essen Branch minutes include a final entry for Joseph Paul Vorst. On July 13, 1930, the records state, “Brother Vorst left today for America. Quite a number of saints didn’t make it to the preaching meeting as they had to see Brother Vorst off. ‘So they say.’”

In 1938, Vorst gave an interview about his emigration. The interviewer described Vorst’s motivation for leaving Germany:

Although by this time his paintings were beginning to receive notable recognition, the spirit of unrest, which pervaded the nation, made him uneasy and dissatisfied; so he decided to leave German shores before his perspective was forced into the shallowness inevitable.

On July 21, 1930, Vorst arrived in the United States aboard the SS Europa. Upon his arrival, Vorst lived among extended family. He settled first in Ste. Genevieve, Missouri, and then later in St. Louis. There, he began to establish himself as an artist, and shortly after his arrival, he became a naturalized U.S. citizen.

While he could not possibly have had much money, Vorst made it a priority to travel to a Latter-day Saint temple as soon as he could. In April 1931, he traveled to Salt Lake City and completed temple work for family members who had died: his father, Paul Johann Joseph Vorst (1864–1918); his uncle, Otto Vorst (1868–1900); and the his younger brother, Karl Paul Peter Vorst (1901–24).

The Great Depression and American Scene Painting

Vorst sped away from the unsettled political landscape of Germany—the waning years of the troubled Hindenburg presidency leading up to the seizing of power by Hitler in 1934—but traded it for the Great Depression in America.

Just as German artists expressed their ideas in art as a way to shape their country, American artists during the Great Depression asked whether art could be used to mold public opinion and encourage action. Vorst fully embraced American Scene art, and his decision to settle in Missouri placed him at the epicenter of two powerful art movements: Regionalism (a focus on the people and landscapes of the heartland) and Social Realism (a related visual sensibility with the added goal of influencing social change).

Depression-Era Calamities: The Great Ohio Flood and the Dust Bowl

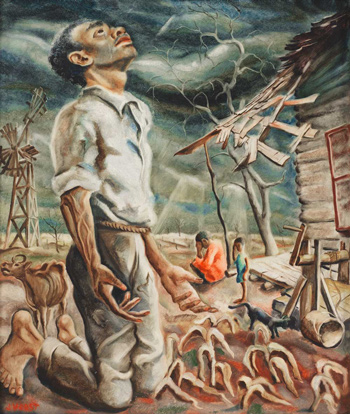

As natural disasters—the Dust Bowl and epic floods along the Mississippi—ravaged the Midwest, Vorst channeled his new American identity into a series of heartbreaking works that chronicle people and animals in stormy crisis. Here his subjects take on a new pathos. Entirely overwhelmed by natural disasters such as crop failures due to drought or storm, Vorst’s subjects fall to their knees.

Already attuned to the plight of the downtrodden and the agrarian Missouri landscape and its inhabitants (including animals), Vorst looked to dramatic narratives that informed and illuminated as well as documented recent tragedies. He used his artwork to show compassion for those who were suffering.

Works Progress Administration and Artists for Victory

With hopes to mitigate the effects of the Great Depression, the U.S. federal government began the Works Progress Administration (WPA), Federal Art Project (FAP), and other federally funded programs that put artists to work. Some of the most noteworthy outcomes of these programs were the murals. Vorst applied for several commission competitions and ultimately created murals for three post offices in Bethany, Missouri; Vandalia, Missouri; and Paris, Arkansas.

In 1939, World War II began. Given his German origins, this must have been a particularly fraught time for Vorst personally, as his immediate family still remained in Europe. Even so, Vorst reacted to the war patriotically, as did many U.S. artists, and he donated the proceeds of his art exhibition to the war effort.

One project, called Artists for Victory, was a natural fit for Vorst, whose work spoke to the issues of the day and attempted to rally citizens to a common cause. Vorst created war posters and participated in wartime exhibitions and charities. He depicted Americans during wartime as strong individuals who, when overwhelmed by circumstance, fell to their knees in prayer.

Towards Peace

Although Vorst considered himself to be wholly American, art critics and the public constantly reconnected him to Germany. This refrain was a subtle prejudice from which he was unable to escape. Still, life settled for Vorst in the 1940s. In his late thirties, Vorst married Lina Weller, another German immigrant, who became his steadying and constant companion. Vorst built a house and began teaching art at Jefferson College, and in 1944, he and his wife had their only child, Carl. At the time, the couple had been married nearly nine years; Lina was 43 years old and Joseph 46.

In April 1947, Vorst mounted a one-man show at the Noonan-Kocian Gallery in St. Louis. For the catalog’s cover, he chose this self-portrait. Instead of holding a paintbrush in his hand as in earlier self-portraits, he held a stalk of cotton. The same year, he showed at the Whitney Museum of American Art, where he exhibited four times among the best American artists of his day.

Then on Wednesday, October 15, 1947, while Joseph Paul Vorst was conducting a choir rehearsal for his Mormon congregation, he suddenly collapsed, stricken by an aneurysm. His wife and three-year-old son were outside waiting for him in their car at the time. Vorst was taken to Lutheran Hospital, where he died of a cerebral hemorrhage.

Vorst didn’t live to see a retrospective exhibition of his work. He exhibited frequently, widely, and well, but he never had the occasion to bring a large number of his artworks together under one roof. In his short life, Joseph Paul Vorst saw the world at war twice, lived through the tumultuous years of the Weimar Republic, suffered through the Great Depression, witnessed natural disasters, and experienced life as an immigrant. Artistically, he took on many media: paintings, drawings, watercolors, murals and mural studies, artists’ books, linoleum cuts, sketchbooks, photographs, sculpture, etchings, and lithograph prints. His style was shaped by his two countries—from German Expressionism to the American Scene’s Regionalism and Social Realism.

Vorst consistently looked to those who were suffering most—the downtrodden, the oppressed, and the underprivileged—and he advocated for them with compassion, hope, and sympathy. For him, the heavens (as represented in the expressive skies of his works) were often a source of radiance and influence on the people below at their most vulnerable times.

Footnotes

[1]

[2]

[3]

[4]

[5]